Aristotle’s theory of knowledge explores the nature of knowledge acquisition, emphasizing the blend of sensory experience and rational inquiry. His foundationalism posits that knowledge rests on indubitable truths, with universals as objects of understanding. The necessity of truth and causality underpins his epistemology, influencing fields like virtue epistemology and modern foundationalism. This framework remains central to understanding Western philosophical thought.

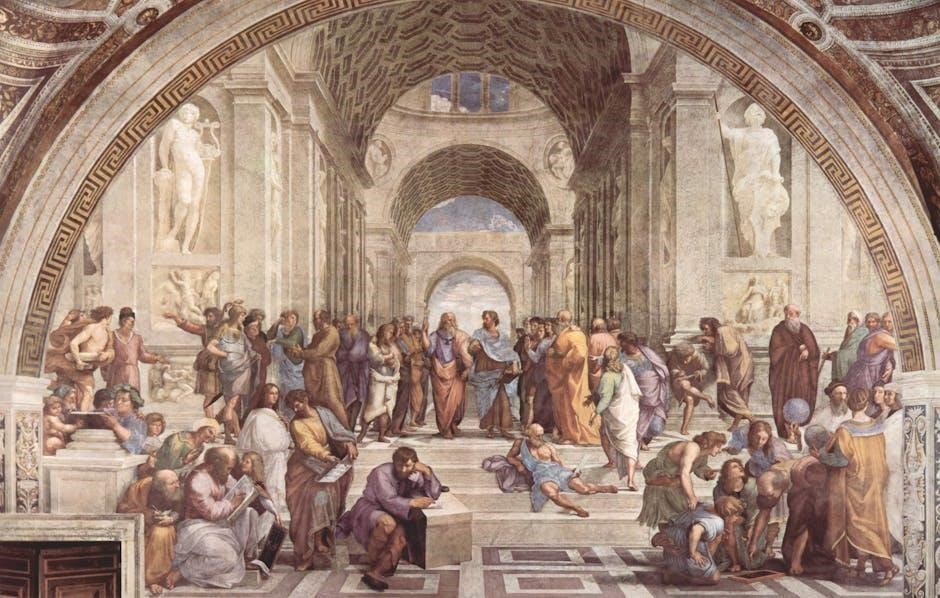

1.1 Historical Context and Importance

Aristotle’s theory of knowledge emerged in the 4th century BCE, shaping Western philosophy’s foundation. His work, influenced by Plato, emphasized empirical observation and logical reasoning. Aristotle’s ideas were pivotal, establishing a framework for understanding knowledge acquisition through sensory experience and rational inquiry. His theories remain influential, impacting fields from science to epistemology, and continue to be studied for their enduring relevance and intellectual depth.

1.2 Overview of Epistemology in Aristotle’s Philosophy

Aristotle’s epistemology centers on understanding knowledge through observation and reason. He distinguishes between theoretical and practical knowledge, emphasizing the pursuit of truth and causality. His theory integrates induction and deduction, advocating for a systematic approach to understanding universals. Aristotle’s episteme, or scientific knowledge, requires necessity and eternity, contrasting with mere opinion. This framework underscores the importance of demonstration and rational inquiry in achieving certain knowledge.

Foundationalism and Indubitable Foundations

Aristotle’s foundationalism posits that scientific knowledge rests on indubitable truths, derived from universals and the interplay of sensory experience and rational inquiry, emphasizing necessity and causality.

2.1 Aristotle and Epicurus: Shared Views on Foundationalism

Aristotle and Epicurus both adhered to foundationalism, believing knowledge must rest on indubitable truths. Aristotle grounded this in universals and rational inquiry, while Epicurus emphasized sense data. Their shared commitment to foundationalism aimed to establish objective truths, though their methods differed. Aristotle’s focus on reason and universals contrasted with Epicurus’ empiricist approach, yet both sought to avoid skepticism by ensuring knowledge’s stability through secure epistemological foundations.

2.2 The Role of Universals in Aristotle’s Theory

Aristotle viewed universals as central to knowledge, arguing they are abstract concepts derived from particulars. Universals represent shared attributes across a class of things, enabling scientific understanding. For Aristotle, knowledge concerns universals, not individuals, as they capture the essential and necessary truths; Universals are thus indispensable in his epistemology, forming the foundation for comprehension and reasoning about the world.

Experience and Rational Inquiry

Aristotle’s epistemology combines sensory experience with rational inquiry, emphasizing the mind’s active role in organizing data to form knowledge through both empirical observation and logical reasoning.

3.1 The Interaction Between Sensory Experience and Reason

Aristotle’s epistemology integrates sensory experience with rational inquiry, positing that knowledge arises from the interplay of these two elements. Sensory experience provides the raw data, while reason organizes and interprets it, enabling the formation of universals. This dynamic interaction is essential for acquiring scientific knowledge, as reason transforms empirical observations into coherent understanding, highlighting the mind’s active role in the process of knowledge acquisition.

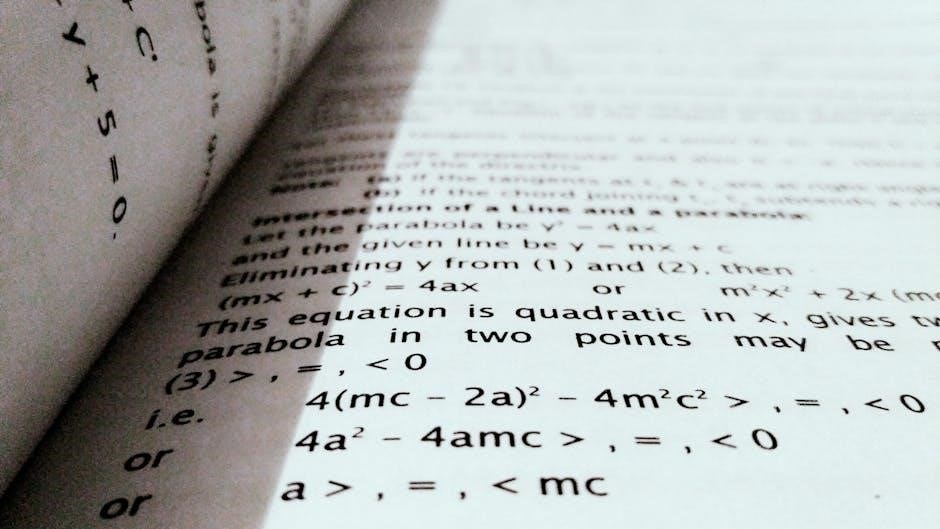

3.2 Induction (Epagoge) and Intuitive Induction

Aristotle’s theory of knowledge emphasizes induction (epagoge) as a method of moving from specific observations to universal principles. In contrast, intuitive induction involves an immediate grasp of first principles. Both processes are crucial for acquiring scientific knowledge, as they bridge empirical data and rational understanding. Epagoge relies on systematic observation and reasoning, while intuitive induction offers immediate insights, together forming a comprehensive approach to knowledge acquisition.

The Four Causes and Knowledge Acquisition

Aristotle’s theory of knowledge incorporates the Four Causes—material, formal, efficient, and final—to explain phenomena, providing a framework for understanding and acquiring scientific knowledge.

4.1 Material, Formal, Efficient, and Final Causes

Aristotle’s Four Causes—material, formal, efficient, and final—provide a framework for understanding reality. The material cause is the substance of a thing, while the formal cause defines its essence. The efficient cause identifies the agent of change, and the final cause explains its purpose. Together, these causes offer a comprehensive approach to knowledge acquisition, enabling a deeper understanding of phenomena and their underlying principles.

4.2 The Role of the Four Causes in Scientific Knowledge

Aristotle’s Four Causes are foundational to his theory of scientific knowledge. They provide a structured approach to understanding phenomena by identifying their material (substance), formal (essence), efficient (origin), and final (purpose) aspects. This method ensures comprehensive knowledge, as it addresses both the “what” and the “why” of existence. The Four Causes are essential for achieving certainty and necessity in scientific inquiry, forming the core of Aristotle’s epistemological framework;

Universals and Their Status in Knowledge

Aristotle viewed universals as central to knowledge, representing common characteristics shared by individual entities. They are objects of understanding, derived from experience but existing independently, forming the basis of general truths.

5.1 Aristotle’s View on Universals as Objects of Knowledge

Aristotle regarded universals as essential objects of knowledge, derived from sensory experience but existing independently. He argued that knowledge must be of universals, not particulars, as universals represent common characteristics shared by individuals. This distinction underpins his epistemological framework, emphasizing that scientific knowledge (episteme) is rooted in understanding universal principles rather than specific instances.

5.2 The Relationship Between Knowledge and Universals

Aristotle’s theory posits that knowledge is inextricably linked to universals, as they are the foundation of scientific understanding. Universals, derived from sensory experience, exist beyond individual instances, enabling objective and necessary knowledge. Without universals, knowledge would lack the universality and objectivity required for Aristotle’s concept of episteme. Thus, universals are indispensable in his epistemological framework, forming the basis of all certain and eternal knowledge.

Scientific Knowledge (Episteme)

Aristotle’s concept of episteme refers to scientific knowledge, which is distinct from opinion. It involves necessary and eternal truths, serving as the foundation of his epistemological framework.

6.1 Distinction Between Episteme and Opinion

Aristotle distinguishes episteme (scientific knowledge) from doxa (opinion). Episteme involves universal, necessary, and eternal truths, derived through reason and demonstration. Opinion, by contrast, is based on changing particulars and lacks certainty. This distinction underscores Aristotle’s commitment to the idea that true knowledge must be grounded in indubitable principles and causal understanding, ensuring its reliability and objective truth.

6.2 The Necessary and Eternal Nature of Scientific Knowledge

Aristotle’s concept of scientific knowledge (episteme) emphasizes its necessary and eternal nature. Knowledge must concern universal truths that cannot change, derived from causal understanding (aitia). This necessity ensures the reliability and permanence of scientific knowledge, distinguishing it from contingent or variable beliefs. The eternal aspect reflects Aristotle’s belief that true knowledge pertains to unchanging principles, forming the foundation of his epistemological framework.

The Role of the Mind in Knowledge Acquisition

Aristotle emphasizes the mind’s active role in organizing sensory data into universals, enabling rational understanding. The mind’s capacity for abstraction and reasoning transforms experience into scientific knowledge.

7.1 The Concept of Nous (Intelligence)

Aristotle’s concept of nous refers to the highest form of intelligence, enabling humans to grasp first principles and universals. This intellectual faculty operates beyond sensory experience, providing intuitive insight into necessary truths. Nous is essential for achieving scientific knowledge (episteme) and understanding eternal, unchanging realities. It represents the pinnacle of human cognitive potential, distinguishing humans from other beings and facilitating the discovery of fundamental truths.

7.2 The Process of Learning and Demonstration

In Aristotle’s epistemology, learning involves a combination of sensory experience and rational inquiry. Knowledge begins with sensory data, which the mind organizes into universal concepts through induction. Demonstration (apodeixis) plays a central role, as it derives knowledge from first principles. This process ensures that scientific knowledge (episteme) is both necessary and eternal, providing a rigorous method for understanding the world.

Truth and Necessity in Knowledge

Aristotle’s theory emphasizes that knowledge must be objectively true and necessary. Truth is established through causality, ensuring that knowledge reflects reality and is universally valid.

8.1 The Objective Truth of Knowledge

Aristotle asserts that knowledge possesses objective truth, deriving from the necessary and universal nature of its objects. He argues that for something to be known, it must be true and incapable of being otherwise. This objective truth is established through causality, ensuring that knowledge reflects reality. Aristotle distinguishes scientific knowledge (episteme) from mere opinion (doxa), emphasizing that genuine knowledge is universal, necessary, and unchanging.

8.2 The Role of Causality in Establishing Necessity

Aristotle’s epistemology emphasizes causality as a cornerstone in establishing necessity. By identifying the material, formal, efficient, and final causes, knowledge transcends mere description, offering explanatory depth. This causal understanding ensures that scientific knowledge is objective, universal, and necessary, distinguishing it from opinion. Through causality, Aristotle’s theory grounds knowledge in an unchanging reality, ensuring its validity and timelessness.

Criticisms and Challenges to Aristotle’s Theory

Aristotle’s theory faces challenges, particularly from Humean skepticism regarding induction and causality. Modern reinterpretations question his views on universals and foundationalism, sparking ongoing philosophical debates.

9.1 Comparisons with Humean Views on Induction

Aristotle and Hume diverge on induction. Aristotle views induction (epagoge) as a rational process, deriving universal principles from experience, while Hume criticizes it as based on custom, not logic. Aristotle’s intuitive induction emphasizes necessity and causality, whereas Hume’s skepticism questions induction’s reliability, highlighting differences in their epistemological frameworks.

9.2 Modern Reinterpretations and Debates

Modern scholars reinterpret Aristotle’s epistemology, engaging with its relevance to contemporary debates. Virtue epistemology draws on his emphasis on intellectual virtues, while foundationalism revisits his indubitable truths. Critics argue his theory of induction lacks empirical rigor, yet his stress on causality and necessity remains influential. Ongoing discussions explore how his framework aligns with or challenges modern philosophical trends, ensuring his ideas remain vital in epistemological discourse.

Contemporary Relevance of Aristotle’s Epistemology

Aristotle’s epistemology continues to influence modern foundationalism and virtue epistemology. His concepts of Nous and the four causes remain relevant in contemporary philosophical discussions on knowledge.

10.1 Influence on Modern Foundationalism

Aristotle’s foundationalism, emphasizing indubitable truths, has shaped modern foundationalist thought. His reliance on universals and necessary truths influences contemporary debates on knowledge justification. The distinction between scientific knowledge and opinion resonates in current epistemology, while his causal framework underpins modern theories of knowledge structure and justification. These elements bridge ancient and modern philosophy, offering a robust foundation for understanding knowledge acquisition and its epistemic grounding. His ideas remain vital in contemporary philosophical discourse.

10.2 Applications in Virtue Epistemology

Aristotle’s emphasis on intellectual virtues, such as wisdom (phronesis) and understanding (nous), has inspired contemporary virtue epistemology. His framework highlights the role of character traits in knowledge acquisition, stressing the importance of habituation and ethical cultivation. Modern thinkers draw parallels between Aristotelian virtues and epistemic excellence, integrating his ideas into theories of intellectual responsibility and the pursuit of knowledge as a moral endeavor, bridging ethics and epistemology effectively.

Primary Sources and Further Reading

Key texts include Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics and Metaphysics. Secondary sources like Kilwardby’s Notuli Libri Priorum and Kosman’s works provide deeper insights into his epistemology.

11.1 Key Texts by Aristotle (e.g., Posterior Analytics, Metaphysics)

Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics is central to his theory of knowledge, outlining the structure of scientific knowledge and demonstration. Metaphysics explores universals and the four causes, essential for understanding his epistemological framework. Other key works include De Anima and Nicomachean Ethics, which complement his views on the mind and virtue epistemology. These texts are foundational for studying Aristotle’s theory of knowledge and are widely available in translations and commentaries.

11.2 Recommended Secondary Literature

Notable secondary sources include works by T. Irwin, J. Barnes, and M-K. Lee, offering in-depth analyses of Aristotle’s epistemology. Hugh Tredennick’s Aristotle: Posterior Analytics provides a detailed commentary. Robert Kilwardby’s Notuli Libri Priorum and Aryeh Kosman’s studies on universals are also essential. These texts offer critical insights and interpretations, aiding a deeper understanding of Aristotle’s theory of knowledge and its philosophical implications.

Aristotle’s theory of knowledge emphasizes the blend of sensory experience and rational inquiry, with foundational truths and universals central to understanding. His enduring influence shapes epistemology.

12.1 Summary of Aristotle’s Theory of Knowledge

Aristotle’s theory centers on the interplay of sensory experience and reason, emphasizing foundational truths and universals. Knowledge, or episteme, is objective, necessary, and derived from demonstrable principles. Aristotle distinguishes scientific knowledge from opinion, stressing causality and necessity. His framework integrates induction and intuition, influencing both foundationalism and virtue epistemology. This synthesis remains foundational in Western philosophy, shaping understanding of knowledge and its acquisition.

12.2 Legacy and Impact on Western Philosophy

Aristotle’s theory of knowledge profoundly shaped Western philosophy, influencing scholasticism and modern thought. His emphasis on reason, universals, and foundational truths inspired debates on epistemology and metaphysics. Aristotle’s ideas on scientific knowledge and induction remain central, impacting fields like virtue epistemology and foundationalism. His legacy endures in contemporary philosophy, offering frameworks for understanding knowledge acquisition and reality, ensuring his work remains a cornerstone of philosophical inquiry and intellectual discourse.